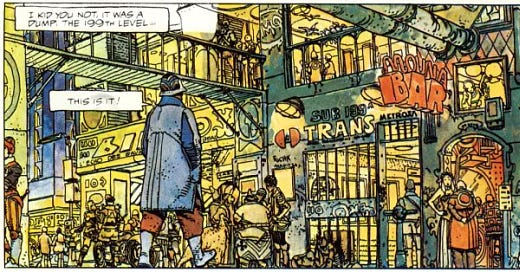

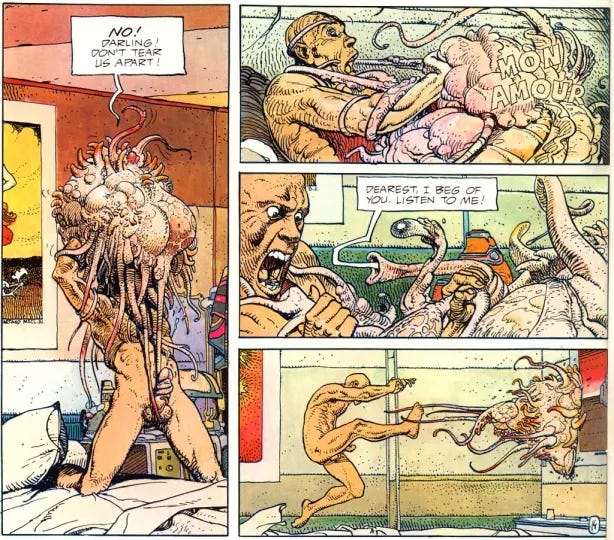

Over my morning coffee, I have been watching this video about how Dan O’Bannon (who wrote the original Alien movie) and legendary French artist Moebius invented the cyberpunk genre in under twenty comic pages. It is about the legendary comic The Long Tomorrow, a short take on a hardboiled detective story in a grimy sci-fi setting, which I love and had read — and read about — before.

This is relevant to me on so many levels, one of which is the fact that I am turning 40 this year on the very day that Johnny Silverhand blows up Arasaka Tower. If that doesn’t call for a huge cyberpunk-themed party, I don’t know what will. So that’s one reason why I am looking at some source material for the genre. Another reason is my own novel, GRIM DEEP, which is obviously in a very similar style to what O’Bannon and Moebius pioneered in 1975.

While the first draft of this novel has been done for a while, I am currently stuck at transcribing about a hundred handwritten pages to compile it all on my computer and start making the first serious edits. Doing this on the side while also writing, producing podcasts and hosting events has been a chore. Which is why I’ve been trying to use Transkribus to train a machine learning model to recognise my handwriting (which is extremely arcane). I have been making some progress on this.

I like how I’m using “artificial intelligence” to help create my novel set in a dystopian future. It feels appropriate. But these experiments also show how unrealistic all of the marketing bullshit is that promises us that computers will do all this work for us in the future. When I look at stuff like The Long Tomorrow from 1975, only the bad predictions in these stories seem to come true. We never get the flying cars, the space colonies or the robots that make our daily lives easier. Instead, the predictions that seem to be coming true are the decline of society and the idea that humans, despite all of our technological advances, always stay the same idiosyncratic, self-serving arseholes we always were.

Wikipedia describes the cyberpunk genre as follows:

Cyberpunk is a subgenre of science fiction in a dystopian futuristic setting that tends to focus on a "combination of lowlife and high tech", featuring futuristic technological and scientific achievements, such as artificial intelligence and cybernetics, juxtaposed with societal collapse, dystopia or decay.

It seems to me that real life always turns out to be a much blander, less interesting version of what the writers, artists and moviemakers imagine. But in essence, we are headed to our own version of the cyberpunk future: A world where technological advancements are employed by the powerful to widen the gap between themselves and the general public. A world where high tech quickly turns into the status quo as the playing field is levelled by the next advancement, while ordinary citizens trudge on, just trying to get from one pay check to the next, occasionally distracted by some entertainment or the media telling them to be afraid right now.

In fiction, worlds like this make for interesting stories as the main characters, usually members of the downtrodden working class, navigate murky places full of the refuse of the upper strata of society — both in a literal, as well as in a moral sense. But when this kind of thing becomes a grim reality for real people, living in the real world, it soon ends up being more horrifying than entertaining.

To some extend, I seek out these realities. I experiment with cutting edge technology all of the time. And I love living in cities that are the focal point and melting pot of these new forces that shape the world around us. This is what made me want to write a novel in this genre, of course. But seeing where we are headed and being, by virtue of my intense study of new technology and its societal impact over the last two decades, largely immune against the PR hype associated with these developments, it does worry me a lot of the time.

Especially what is happening in the information space worries me. Cyberspace is, as you know if you know your cyberpunk, where the real kings are crowned and the worst wars are fought. What started with people just being misled about the products they buy — how long will this car last? is this digital assistant actually useful? how buggy is this software? — has now extended towards almost all aspects of social life.

One of the mainstay features of cyberpunk literature is the idea that, in the future, areas of state and corporate interests will merge. That corporations will become the state. With undeclared proxy wars being fought by PMCs and corporate media and corporate social media censoring public discourse — both in the interest of state officials — it feels to me that we have now reached this future.

Please indulge me on a little thought experiment here. Imagine that, a few decades ago, I’d pitched you this backstory for a novel or a film set in the near future:

A superpower exerts political influence on a country halfway around the world to further the interests of its own corporations (some of these interests exist in cyberspace)

Seeing its own corporate interests threatened, a rival superpower uses PMCs under the cover of plausible deniability to invade this country, which it shares a border with

This escalates to a full-on proxy war that includes spec ops missions to attack, and destroy, infrastructure in other countries that is serving the interest of the conflict parties

Both states widely use control over media sources within their respective spheres of influence to sow distrust about their enemies and hide their real goals in the conflict

On the ground, the war is being fought increasingly by private military companies; states work together with media corporations to blanket cyberspace with propaganda

Wouldn’t that be an amazing backdrop for a cyberpunk story? It also accurately describes the reality we now live in. You can see much of the unholy state-corporate media union in action right now when it comes to the Seymour Hersh story. This morning, I’ve read that it is now censored by Facebook, obviously because it clearly contravenes US national interests.

Facebook’s head of “Misinformation Policy,” Aaron Berman, came from the CIA. “It's instructive to remember that if the US were involved in the Nord Stream bombing, it would have to have been under the cloak of plausible deniability,” explained Benz. “The agency mostly directly tasked with plausible deniability is the CIA. Lo and behold, the head of Facebook's Misinformation Policy, under which Hersh appears to be censored, is a 17-year veteran of the CIA.”

Why, though, would Facebook and its allies risk the “Streisand effect,” which is when the demand for censorship draws more rather than less attention to stories? The answer may come from the Hunter Biden laptop experience. What was important for Biden supporters was for the laptop, which plainly did not come from a Russian hack, to be framed as “Russian disinformation,” in order to discredit it. The laptop might get more attention, but it would be framed as disinformation. The same thing may be happening with Hersh’s story about Nord Stream.

As I’ve said before, I have no idea if Hersh’ story is true. But the more stuff like this happens, the more convinced I am becoming that it actually is true. Michael Shellenberger, writing in Public, sums my own reasoning up quite nicely when he writes:

Some amount of censorship, or “content moderation,” is inevitable. The vast majority of Americans would support many forms of content moderation. But censoring a debate over who blew up a pipeline does not meet the threshold of needing to be censored. And instead of explaining, Facebook sends readers to an article in Norwegian by its Norwegian fact-checker, Faktisk, which is run by a Norwegian journalist.

In other words, Facebook has decided that a Norwegian journalist is right and Hersh is wrong. And maybe Hersh is wrong. Maybe the Norwegian journalist is right. Whatever the case, it should not be up to Facebook to decide. It’s a debate that should proceed without Facebook’s intervention.

What’s more, Hersh is infinitely more independent than Facebook’s Norwegian fact-checker. The fact-checking organization is a partnership with a Norwegian government-owned media company, NRK, which has a direct self-interest in censoring the story.

In case you haven’t been paying that close attention to the story, let me quickly bring you up to speed: Hersh says Norway helped the US blow up Nord Stream. Again, I do not know if that is true. But one thing that is obvious is that Norway has benefitted massively from the results of the sabotage.

If the mission of a journalist is to inform the public, than this new breed of “fact checkers” is now the anti-journalist. They exist to hide information and confuse the public. Welcome to our new cyberpunk reality, everyone!