Thoughts on Artificial Intelligence (And on Substack Notes)

Why AI is less revolutionary than people think and trying to answer the question if Substack Notes is worth it

As I am sitting here at my desk this morning and looking at the rain falling on the street outside — my wife has just left for a big cardiology conference in Mannheim and I am temporarily a bachelor again for a few days — I am contemplating that I haven’t written for this newsletter in way too long. Things, as usual, have been very busy and they haven’t been going to plan. Not in a horrible way, just in the usual confused mangle that is the life of a freelance journalist.

As I am contemplating all of this, I am listening to the wonderfully melancholic soundtrack to Disco Elysium by British Sea Power1, which is now finally on Spotify. I recommend you check it out, it is a wonderful album.

At this point, I would like to promise you that I will definitely write newsletter issues more regularly in the future. But with the state of my current work planning much resembling the state of mind of the detective in the aforementioned Disco Elysium, promising anything like that would be stupid. So let’s just take it day by day for now, shall we?

Social Media, Dungeons & Dragons, Bouldering

Before I get to some tech and journalism topics, I am going to update you on what has been happening in my life. I see this as an important instrument of accountability, but also a way to connect with my readers. If this kind of thing doesn’t interest you, you can just skip to the next heading, I won’t take it personally. After all, I might be doing all of this because I’m actually driven by egomania — it’s a distinct possibility you always have to be wary of with writers.

I’m not going to go into the writing I have published and the podcasts I have released since you last got a newsletter from me. That would just be too much and you can find that information on my website, if you are interested. But I would like to mention that I’ve started integrating my forum with my blog some more to facilitate reader comments. I am embedding automatically generated forum posts for items on my blog and on the podcast show notes. You can see this in action on the end of this show notes page, for example. At the moment, these automatic posts are cluttering the forum a little bit, as a backlog of them for old content of mine — of which there is a lot, even when only looking at stuff I made since I started freelancing in 2019 — is generated, but that will settle down over time. This move to better integrate the forum into what I do every day is very important to me. I’ve been trying for years to get away from social networks like Twitter and its Fediverse alternatives and I am still trying to move everything to software I have direct control of without losing too much public reach. But more on my futile attempts to pry myself away from Twitter later.

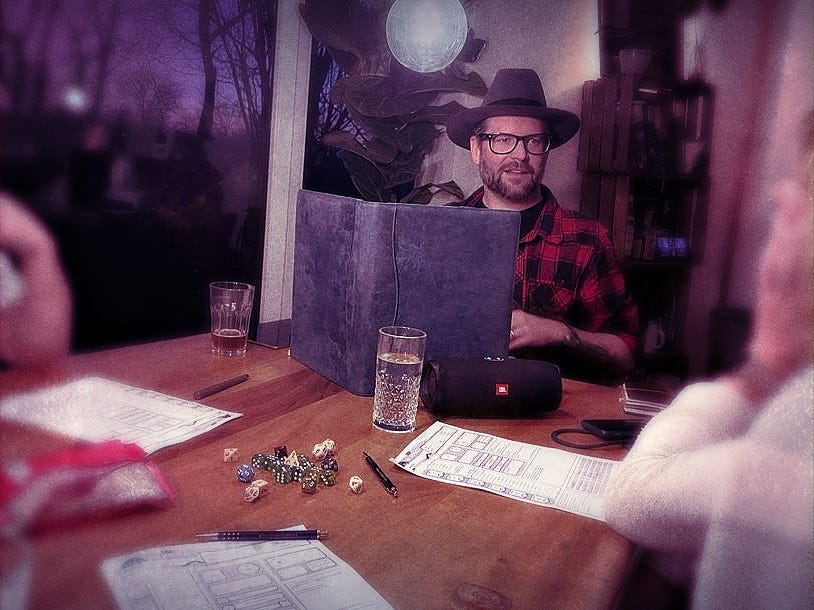

Another thing that has happened recently is that my friend Halefa has, by talking about it for years, finally gotten me to watch Critical Role and now I’m completely hooked on it. I am almost to the end of episode 16 of their first campaign as I write this. Critical Role, in turn, has gotten me interested in Dungeons & Dragons again, which I haven’t played for decades. So I’ve designed my own D&D world and, over the Easter weekend, DMed my first ever game. Which was a lot of fun, not only for me, but also for my players it seems, as they are eager to continue the story. We will do this remotely, because some of my players live 500 kilometres away from my office here in Düsseldorf. This has let to me trying out a lot of software people use to DM games these days, including “artificial intelligence” — more on this later, too.

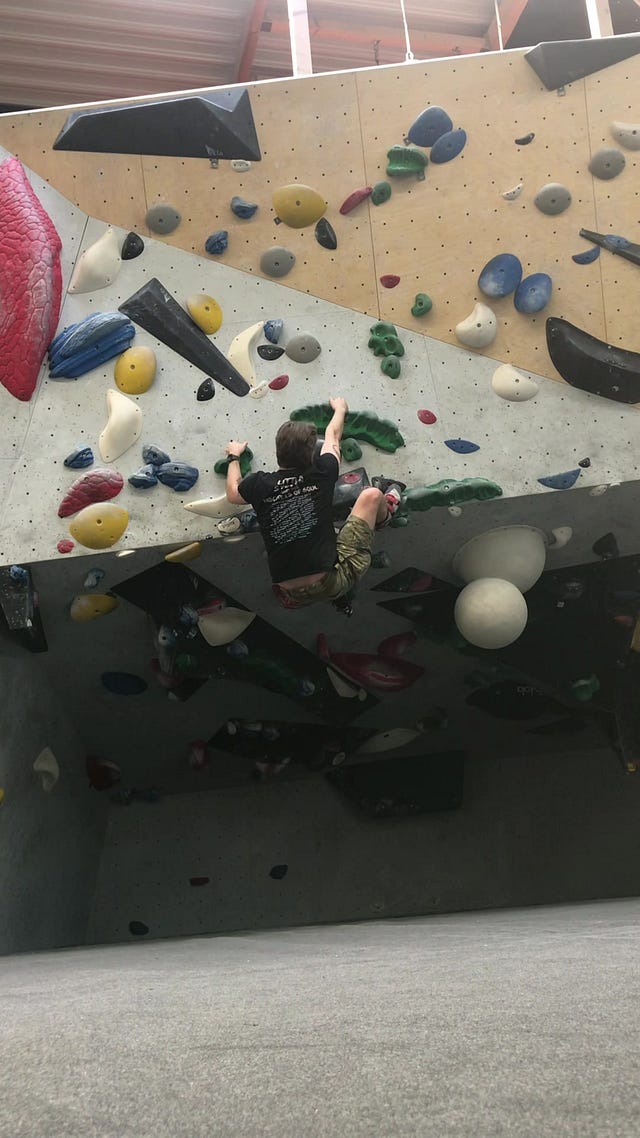

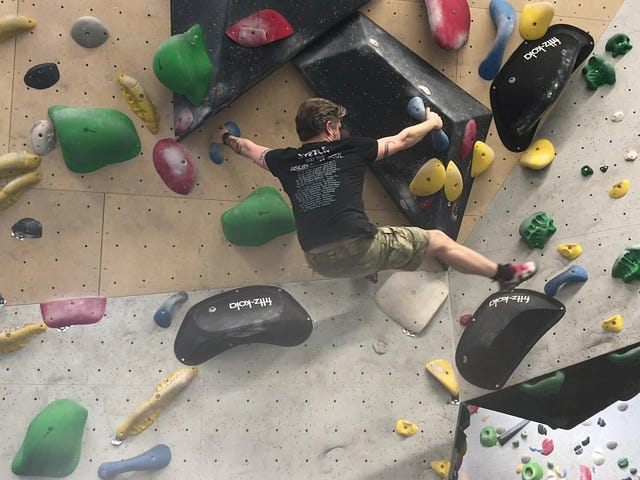

When I started freelancing more than four years ago, I resolved to not cancel exercise because of work commitments — this kept happening when I was employed and it was one of the main reasons for me quitting my job at Heise back in the day. When the pandemic hit, I saw people who were in fear of getting sick but, at the same time, were massively neglecting their health by staying home and not exercising, and I decided to double down on my exercise plans instead. It has worked very well for me. I have not let work interfere with my sports routine and I’m exercising four to five times every single week now. I’ve lost around 12kg over the years and gained a chunk of it back in muscle mass. I am eating more than I have before, but I’ve nonetheless steadily lost body fat — simply by exercising all-out every single time (running with 10kg weights in a plate carrier, for example). Then, last autumn, I met this Swiss girl at a wedding and she had the most amazing biceps. I was very envious of her upper arms and asked how she came by them. She said she went bouldering twice a week. Now, once again, Halefa’s and Jonathan’s influence on my life made itself felt, as they had also talked about bouldering to me previously. So I decided to try it out.

I’ve been bouldering every week since November. After an initial culture clash with the zoomer hipster culture pervading this sport, and some difficulties in ordering the needed equipment online, I am now making some progress. I’ve skinned my knees a lot, hurt my hands and I’m developing a lot of callouses. But I’ve also graduated from the easiest level of routes available at my gym and I think I’m starting to get the hang of some of the intricacies of this sport.

Even though I am mostly doing this to build some arm muscles, to complement my already well-developed leg muscles I got from running regularly, I am also appreciating the puzzle nature of this kind of climbing challenge. Even if I am not primarily trying to compete earnestly. The weekly climbing is also doing good work combating my fear of heights and helping with flexibility — which is one thing you actually lose if you primarily run and do weight lifting exercises.

As you can see, I am keeping busy, not only at work. Which is why sometimes things like this newsletter take a backseat. But enough about me and my life, let’s get to some recent developments in the tech world and what I think they mean for our future.

Some Thoughts on What People Keep Calling “Artificial Intelligence”

AI, or “artificial intelligence”, is the new hype in tech. It’s gotten so big, it has even reached mainstream publications. People on the street are wondering if AI will threaten there jobs. Bad journalists have been fired and replaced by machine learning algorithms. Artists are in open revolt.

Anybody who has followed Silicon Valley news for decades, like me, knows that whenever technology gets hyped like this, it inevitably falls short of expectations. Usually very much so. This is especially true for two-letter abbreviations. Remember how VR was going to replace all user interfaces? Or the impending AR revolution? Google Glass, anyone? None of this has happened. Or it kind of has. But differently. These overhyped technologies, without fail, fall short of revolutionising our lives, but they always get integrated into minor parts of how we live our lives in the future. Often in niche ways. The things that actually revolutionise society — like changing the user interface of an already established device slightly and drastically improving its polish, thus making it actually useful all of a sudden — are never preceded by a huge wave of hype from the technorati. They just happen, as people organically decide they like a product, buy it en masse and integrate it into their daily routines. In those cases, the hype always follows a product getting popular first. When something isn’t popular yet and you need sales people and journalists (mostly the same in Silicon Valley these days) telling you why you need it in your life, that’s usually a sign that you don’t. If something is actually useful, people almost all of the time tend to figure it out without journalists having to tell them.

Now, I’ve talked at length about why “artificial intelligence” is a dumb name.

TL; DR: We do not have the technology to make anything that’s intelligent and probably won’t in your lifetime or mine. We need to understand how the brain works, first. And we’re still discovering new types of neurons, so that’s ways off. We also don’t understand what “intelligence” actually constitutes. This includes basic philosophical questions about what it means to be alive. Questions humanity has tried for literally thousands of years to answer, not making much progress in the process at all.

So if AI, or “artificial intelligence”, is a misnomer, what should we call it instead? I’m going with powerful computing for the time being. Because, essentially, that’s what we mean when we are talking about AI. When sales people — be they actual sales people, scientists or journalists — talk about “artificial intelligence”, what they mean is essentially a whole lot of computing power, shitloads of data and a way to process this using basic statistical methods. That’s what AI boils down to in the end.

But AI is also, more importantly, a user interface. User interfaces have held computing back for half a century now. Fifty years after the introduction of the personal computer, we are still using the keyboard and mouse method as our main way to interact with our computational devices. Touch screens, the biggest innovation in this field, are nothing more than a clumsy sausage-based mouse. VR has gone nowhere in the last twenty years. Voice interfaces are limiting and their own hype is rapidly wearing off as well. Meanwhile, computing power has exploded. But consumers have very inadequate ways of accessing all this computing power. In many ways, the smartphone apps we use today are more clumsy and less powerful than what I can do in a Linux terminal, which uses an interface that was invented in 1971, long before I was born. The power inherent in modern CPUs, GPUs and the abundance of volatile and permanent storage in these computing systems is kneecapped by interfaces designed by or for morons and additionally hampered by shit like dark UX patterns.

What people call AI is basically just a better user interface to access these resources. We could have done efficient statistical analysis on large amounts of data decades ago. No matter what the sales people tell us, we don’t need the cloud for this. Besides, the network was already the computer in the ‘80s. And people already did these things — ”artificial intelligence” is, by no means, a new concept. Things like ChatGPT are so surprising and remarkable, and feel so revolutionary, because they are a new interface to unlock this potential that was already slumbering in computers for decades. The remarkable thing about AI is not what it can do, but that it took us so long to actually use the potential of the massive computing resources we have been deploying and the mountains of data we have been collecting on everything.

When it comes down to it, machine learning algorithms are simply a way of accessing the knowledge about things and events that is stored on the internet. And of using this knowledge to create novel visual, textual (and to some extend auditory) representations of it. In the science fiction literature of the ‘70s and ‘80s this would have been described as “creating avatars from the fabric of cyberspace” or something similarly romantic. The heavy lifting is done by, when look at it in detail, quite simple statistical tools that have been around for centuries in some instances. There is really very little magic about it. It is mostly a question of — finally! — using the infrastructure we have built at scale. And making it accessible to everyday users.

This also explains why “artificial intelligence” isn’t actual intelligence. Or why it can’t create things or ideas that are new. Everything it does is derivative. All of it is based on the intelligence, or stupidity, of what people have put on the internet in the last few decades. But this also explains why using these algorithms to write scientific papers or journalistic stories is unconscionable: What you are doing there is using a biased statistical model to produce things based on a very biased dataset. The things AI creates are as biased as the products of human labour could ever be. But with the actual work of humans you have some insight into their specific biases — which is why transparency about such things is so important in journalism and science — with AI you have no way of knowing. You don’t even have the cold, hard logic of old-fashioned statistical analysis with all its own biases to meta-analyse, because the whole point of AI algorithms is to do this stuff at a scale that humans can’t even comprehend. AI is extremely dangerous in this way.

Which doesn’t mean these systems can’t be useful. In art, for example, none of the above matters. Which is why things like the Stable Diffusion based system Midjourney is very useful for creating things like D&D character portraits in minutes and for a few cents, where commissioning an artist would have taken a few months and probably costs hundreds, if not thousands, of euros. Here, I don’t care what bias the AI has. I just plug away at it until I get a picture that is acceptable to me. For use in a private context.

Machine learning systems can also be interesting for fictional writing. Products like Laika can help writers find inspiration and, since fictional writing is art as well, don’t carry the severe accountability and reliability consequences for society that non-fiction writing based on AI does. As a side note, if you are interested in Laika and similar tools, you might enjoy this Substack written by the Laika developers:

In science and industry, machine learning can be used for great effect when it comes to data analysis or process management. It is just a variation of established statistical methods, after all. A way of using them at a grander scale. It seems prudent to only use these systems when the outcome is all you care about. In situations where you need to know how this outcome has been arrived at, on the other hand — reports of events, understanding the nature of the universe and the human condition, elections, medical procedures, political or corporate decisions to curtail civil rights and personal freedoms, just to provide some examples — employing a black box that makes decisions based on raw statistical systems and data you don’t understand is quite unethical.

Nobody cares if these unknown biases influence the homework assignment some kid has had ChatGPT write because of laziness, or if the poster on your wall was created by DALL·E instead of an actual artist. But if you get your news or scientific papers from systems like this, we are in trouble. Because systems that are based wholly on a scientific analysis of the status quo of society and the total of its digital knowledge can’t arrive at new insights. Nor can they speak truth to power. They therefore can’t be relied on for scientific progress or provide a viewpoint you can trust when things come down to brass tacks.

Because “artificial intelligence” as we know it today, despite what the hype says, is infinitely closer to a really big Excel sheet than it is to Lt. Cmdr. Data.

Substack Challenges Twitter — Or Does It?

Let’s move on to a somewhat lighter and less theoretical topic that’s been on my mind these past few days. Substack, the company that provides the software this newsletter is published with, has launched a new feature called Notes. It is, essentially, a Twitter-like social network for writers and readers on the platform. Substack writers can use it to share short messages, media and links with their readers and other writers. Currently, to follow someone on Notes means you need to subscribe to their Substack publication, too. This makes the whole thing a bit cumbersome. And naturally, despite Substack’s growing audience lately, it’s still a ghost town compared to any other social network. Therefore, I remain sceptical about this idea, but I am willing to try it out. Anything to get away from Twitter2, really.

Speaking of Twitter, it seems that the social network company has taken this launch as a direct attack on its business. After initially blocking all Substack links outright, one can now post them again now, but tweet embeds remain broken within Substack newsletters.

A six-day row between Twitter and Substack has come to an uneasy truce after the social media site stopped censoring links and searches for the newsletter platform following the latter’s decision to launch a rival microblogging service. The conflict started last Wednesday, when Substack announced a new feature, “Substack Notes”, which offers a Twitter-like experience for the company’s user base of newsletter authors and their readers, some of whom are paying subscribers.

But the company’s efforts to compete with Twitter brought an immediate response from Musk himself. Over the Easter weekend, any tweet containing a Substack link was algorithmically deprioritised, blocked from being liked or retweeted, and hidden in search. Searches for the term “substack” itself were automatically replaced with searches for the word “newsletter”. And many users who did manage to find and click on a link to a Substack site reported being warned by Twitter that the service was “unsafe or malicious”.

Unfortunately, this infighting might have ended the great Twitter Files reporting Matt Taibbi has been so busy with and which has exposed, among other things, the extend to which government organisations, particularly in the US, have tried to manipulate the public’s perception of reality.

Taibbi, who like virtually all Substack writers, relies on Twitter to advertise his writing, said that, given the choice between Twitter and Substack, his decision would be obvious.

I’m staying at Substack. You’ve all been great to me, as has the management of this company. Beginning early next week I’ll be using the new Substack Notes feature (to which you’ll all have access) instead of Twitter, a decision that apparently will come with a price as far as any future Twitter Files reports are concerned. It was absolutely worth it and I’ll always be grateful to those who gave me the chance to work on that story, but man is this a crazy planet.

He seems to have asked Musk directly what was happening, pointing out that he would side with Substack — a company that originally employed him, helping him to go freelance in the first place and now enables him to earn a living directly from his subscribers — to which Musk apparently reacted by leaking his late night encrypted Signal chat with Taibbi on Twitter. He later deleted the tweet, but the damage has been done, I think3.

Musk, in what appears to be a Signal chat, asks Taibbi: “You are employed at Substack?” Taibbi explains that his subscribers pay him and that he was one of the first “Substack Pro” writers, who were given an upfront payment for a year in return for giving Substack 85 percent of subscription revenue. Taibbi also asks if Twitter will fix an issue where his Twitter Files threads were being deleted, and Musk says that will happen.

I’ll wait for Taibbi to chime in on this, as he’s currently on vacation, but if this has indeed killed his participation in the Twitter Files reporting, that’s a huge loss for all of us. If it happens that way, I am inclined to say Substack Notes wasn’t worth it — based on my estimation of its chances to succeed and the material Taibbi has dredged up from the Musk-provided internal Twitter data to date.

Before this whole kerfuffle started, Taibbi recorded a very insightful podcast episode with Walter Kirn on his recent MSNBC interview and how, and why, most of the legacy media in the US doesn’t want to touch The Twitter Files with a ten-foot pole. It is well worth a listen. Aside from the insight into Taibbi’s work, I find Kirn to be one of the most thoughtful and literary-minded Americans I’ve heard in a long time. I don’t agree with these guys on a host of topics — including their general take on life in the US and in Europe — but I find their perspective, and analysis, very inspiring.

Alright. I think I’ve rambled on long enough. I hope this newsletter has made you think and given you some ideas of your own. Or has simply informed you a tiny bit, somehow. In any case, please let me know via email, a comment or even through Substack Notes, if that works for you.

Until next time…

Technically, they are now, because of a dumb marketing move, simply called Sea Power.

As I’ve written about before, I am not against Twitter pe se. Nor do I think it’s dying, no matter how many publications like Platformer now have built their whole audience around this idea. I just want to get to a place where I control more of my social media content. Going to Substack isn’t ideal, of course, but as a smaller company, I feel more comfortable here then I do on Twitter. I’ve been uncomfortable with Twitter years before Elon Musk took over, after all.

I find it very interesting that places like The Verge published these private messages. I personally think they are well within their right to do so as this stuff is newsworthy in my opinion. But considering the outrage that used to come from these outlets — as late as the onset of the very Twitter Files that started all of this, where Taibbi published internal Twitter messages of specific employees he named by name — when someone published personal messages from people they liked, this is the height of hypocrisy. Not that this surprises me anymore.